The

1637 Scottish Book of Common Prayer

King Charles I, and his father King James before him, had throughout their

reigns wished to prescribe fixed forms of liturgy and prayer (as had long

been in place in England) to their native Scotland.

This was, as any student of history should know,

a time of great religious upheaval and controversy. In Britain the forces

of the Anglican Church were striving to maintain their relatively traditional

liturgy against the rising tide of the Puritans in England and Presbyterians

in Scotland, who both wished a state religion which was much more "Protestant"

in character. In the background there was the always-present danger of

a return to the Papacy.

King Charles was firmly of a mind to extend Anglican

forms to Scotland, particularly as expressed in the Book of Common Prayer,

and the great majority of the Scottish people were equally determined

to resist. Charles was not one for compromise, and so had the Scottish

Bishops, with the approval of Archbishop William Laud, draw up a Book of Common Prayer for Scotland.

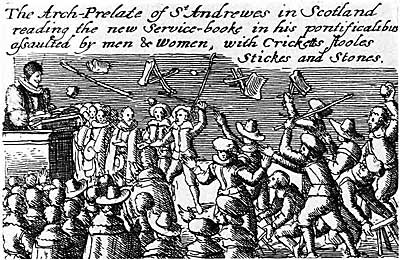

This Book was promulgated in 1637 and was immediately denounced by the

Scottish people; it was never even put into use.

|

|

|

|

This was one of the more important of the events

which led to the Puritan Revolution of 1645, and Charles' overthrow and

eventual beheading.

|

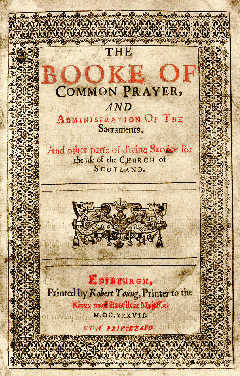

A

1712 reprint of the 1637 Scottish BCP. |

If

that was all there was to this book, it would likely be only an historical

curiosity. However, after the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688

which overthrew James II and brought William and Mary to the throne, the

Church of Scotland was delivered firmly into the hands of the Presbyterians,

leaving those who preferred Anglican forms with no home. These formed

the Scottish Episcopal Church, and began to take as their Prayer Book

the old 1637 Scottish Book of Common Prayer. It was reprinted several

times in the 1700's, and by the mid to late 18th century forms based on

this book were in common use in the Scottish Episcopal Church. So when

Samuel Seabury came in 1784 to the Scottish Church to be ordained the

first American bishop, he was urged to take these Scottish forms as the

basis for the American Episcopal liturgy. He did, and as a result this

book can be seen as a direct ancestor of the American Book of Common Prayer

- particularly with regards to the Communion Service. We have online the

1764 Communion Office of the Scottish

Episcopal Church - the successor to the one in this book, and the predecessor

of the one in the first U. S. Book of Common Prayer, and also Seabury's

nearly identical Communion Service, which

he used as Bishop of Connecticut.

The book is basically

a moderate revision of the then-current Prayer Book: the Book of 1559, as

revised in 1604. There were a large number of changes, but the vast majority

of them are quite minor. The more significant changes include:

- Most (but by

no means all) of the scripture readings from the Apocrypha were removed

as a concession to the Presbyterians.

- Another concession

was the use of the term "Presbyter" to replace "Priest"

or "Minister".

- The Communion

Service was rearranged significantly to bring it to be more in line

with the original 1549 Book.

- The water of the

baptismal font was directed to be changed at least once a month, and

a form of blessing provided for the new water.

- Biblical texts

were taken for the first time from the Authorized, or King James Version

of the Bible.

- The general tone

of the book, particularly in its rubrics, is more prescriptive.

These

changes may be seen by comparing this text with that of the 1559 Book. This book is listed in David

Griffiths' Bibliography of the Book of Common Prayer as 1637/9. The Internet Archive has two copies (both from the Benton Collection at the BPL) available as PDF graphics: copy 1; copy 2.

The

Communion Service is also online in

modern spelling. Two identical reprints (from 1904

and 1909)

of this book (Griffiths 1904/6) with a lengthy introduction by James

Cooper are available from Google Books in PDF graphics and plain text

formats. Google Books also has the

1712 reprint pictured above as PDF graphics (Griffiths 1712/7). We also have online Scottish Liturgies of the Reign of James VI, which presents a very different and much earlier draft of this book, along with an extensive historical introduction and commentary.

Notes on the

text:

The basic text was first taken from either a reprint of the 1559

BCP, or from Liturgiae Britannicae, by William Keeling (Pickering,

London, 1851). This text was then compared with an actual copy of the

original, and changed to agree with the original wherever necessary.

My copy of the original 1637 text has three or four pages missing; in

those cases, the comparison was made instead with a 1712 reprint (title

page above, Griffiths 1712/7). The original text used Roman type for headings

and the rubrics, and blackletter ("Old

English") for the basic text of the services. Since blackletter

is not a font commonly found on computers (and isn't particularly readable

anyway), we have replaced the blackletter of the original with Roman,

and replaced the Roman font of the rubrics with italics. The original

spelling and punctuation has been maintained throughout (the 1712 reprint

updates the spelling, but not punctuation or capitalization). There are

several pictures of pages of the original so you can see just what it

actually looks like. Additionally, a PDF graphics version is available from the Internet Archive.

It is

to be expected that this edition, which is nearly 400 years old, uses

some archaic English words. What might not be expected is that certain

words used here have entirely different meanings nowadays than they did

in the 1600's. The meanings of any particularly unusual words, or words

whose meaning is very different today, are given in the text.

|

(photo by web author)