CHAPTER LXVII

THE. ALGONQUIAN FAMILY.

THE Algonquian family occupied formerly a more extended .area than any other in North America. Of the several divisions, geographically, the northern is the most extensive, stretching from the extreme north-west of the Algonquian area to the extreme east, chiefly north of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes, including the Chippewa-a popular adaptation of Ojibway-group, which embraces the Cree(?), the Ottawa, the Chippewa, and the Missisauga; the Algonkin group, comprising the Nipissing, the Temiscaming, the Abittibi, and the Algonkin. The north-eastern division embraces the tribes inhabiting Quebec, the Maritime provinces, and the State of Maine. Here we find the Micmac belonging to the Abnaki group. The western division comprises three groups dwelling along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains, the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Arapaho, and the Cheyenne.

The Sault Ste Marie Mission at Garden River was begun between 1831 and

1833 by the Rev. William McMurray (1810-1894). A church was built by

the Government. A few years later he was obliged to retire on account

of ill-health. The mission then passed into the hands of the Rev.

Frederick Augustus O’Meara, who ministered to the Indians at Garden

River until 1841, when he was removed to Grand Manitoulin Island, in

Lake Huron. Here the Canadian Government endeavoured to concentrate the

neighbouring Indians in 1840 and 1841, after the mission at the south

end of Lake Superior had been discontinued. O’Meara was born in

Dublin, Ireland, and obtained his. master’s degree from Trinity

College, Dublin. Shortly after his ordination he answered a call made

by the bishop of Dublin for young men to do missionary work in what was

then Upper Canada. After a year or two as travelling missionary he was

asked to take charge of the Indians on the Georgean Bay and Lake Huron

generally. For a year he lived at the Sault Ste Marie. At the request

of the late Bishop Strahan and the Governor of Canada he accepted the

position of Government chaplain to the Indians on Grand Manitoulin Island

and remained there a little over twenty-one years. The work in his new

field was richly blessed. His services to the Church in his different

translations of the Prayer Book and of portions of the Bible, with his

untiring labours among the Indians received high commendation from the

bishop of Toronto[1].

It was soon after 1841 that Dr. O’Meara translated most of the Liturgy. The first edition was published in Toronto in 1846 for the S.P.C.K. 467 and 50 pages, 8vo. A revised edition appeared in 1853, entitled:

* Shahguhnahshe | Ahnuhmeähwine Muzzeneēgun | Ojibwag anwawaud azheühnekenootah- | beēgahdag. | Toronto: printed by Henry Rowsell, | for the Venerable Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. | London. | MDCCCLIII.

A literal translation of this Chippewa title, according

to Pilling, is: English | Prayer Book | the - Chippewas, as their language

- is so - translated - and - put - | in - writing. Title, reverse blank.

The text, in roman letters, is entirely in Ojibwa, except English and

Latin headings. It occupies pp. 3-272, i-ccclvi; page, 3¼ x 6¼;

paper, 4½ x 7¾ inches. Of the pages, numbered with roman

numerals, pp. i-cxx contain the Administration of the Sacraments: Ewh

kechetwah Shahkuhmoonengawin. Pp. cxxi-cccxxx the Psalms. or Psalter

of David: Oodahnuhmeahwine Nuhguhmoowinun owh David, i.e. literally

translated: His - religion songs that David. Then follow on pp. cccxxvii-ccclvi

Nuhguhmoovinun, i.e. songs or hymns.

[1] A most interesting account of the work of this mission is found in James Beaven, Recreations of a Long Vacation, or a Visit to Indian Missions in Upper Canada, London, 1846; 196 pp.; illustrations; small 8vo.

Griffiths 129:1; this language is Ojibwa

Another edition was published in 1883(?) 1-643 pages; colophon, p. (644), 12mo. In this edition the Benedicite Omnia Opera and the Athanasian Creed are omitted.

For a number of years the American missionaries among the Chippewa used Dr. O’Meara’s translation. Among others, the Rev. James Lloyd Breck (1818-1876), one of the earliest episcopal missionaries among the Chippewa in Minnesota, states in a letter, printed in Bagster’s Bible of Every Land, second edition, p. 452 :

“We use the Anglican Prayer Book, which has been translated into Ojibway by an English missionary, the Rev. Fred. A. O’Meara, D.D., who ministers to the Chippewas on the Manitoulin Islands, in Lake Huron.”

Dr. O’Meara translated also the whole New Testament. parts of the Old; Hymns; and wrote several other tracts in the Ojibwa language.

After a faithful service of a little over twenty-one years at Manitowaning, on Manitoulin Island, it became evident to O’Meara that the English Government was about to hand over the charge of the Indians to the Canadian Government and that the latter would abandon the establishment at Manitowaning. Consequently he resigned and accepted an appointment in the Diocese of Toronto. For five years he was in charge of the United Missions of Georgetown. Stewarttown and Norval; and was then called to the rectorate at Fort Hope, Ontario, which he held at the time of his decease in December, 1888. In his work of translation, Dr. O’Meara found that while there were certain scriptural terms peculiar to the Orient which had to receive a somewhat peculiar rendition, such as Wigwam for Tabernacle, there was not a single thought or fact that could not be faithfully conveyed to the Indian mind in its own tongue[2].

Griffiths 129:6 (1882, a number of reprints)

Griffiths 129:4; Griffiths considers this to be the Ojibwa language.

Pp. 1-72 contain the portions of the Book of Common Prayer; 73-101 hymns. Two later editions were pubblished, one in 1886 reading: Anamie-muzinaigun | Wejibuewising | Wejibuemodjig | chi abadjitowad. | Ka-ajanaangag, | 1886. English imprint; Detroit, Minnesota. | The Record Steam Printing Office | 1886. Title, reverse blank; text, pp. 1-148. 18mo. Prayers, pp. 1-74; hymns (with half-title Nagumowinun), pp. 75-148. Most of these hymns were from the collections of the Revs. Peter Jones, James Evans and George Henry, though a few are original translations.

A reprint, with corrections and additions, of this 1886 edition appeared from the same press in 1895. 130 pages. Pp. 59-130 contain the collection of hymns, 87 in all.

In a letter dated Washington, D.C., February 28, 1912, Dr. Gilfillan writes as follows;

“ ... I had gone to the Reservation in June, 1873, sent there

by the Bishop, and as there were only a very few copies of Dr. O’Meara’s

large Prayer Book to be had and many of the expressions in it were not

Ojibway, it was necessary to have a smaller, handy book, containing only

the parts in daily use. . . . I got T. A. Warren[3], the Government

interpreter, a leading half-breed, Paul H. Beaulieu[4], and

also, part of the time, Rev.

En-me-ga-bouh or John Johnson (an Ottawa by birth),

the Ojibway clergyman (died 1902) in charge of the local congregation.

. . . To these I read sentence by sentence those parts of Dr. O’Meara’s

large Prayer Book which we wished to translate. . . . In cases of doubt

recourse was had to a full-blood Ojibway, Ki-chi-bi-ne, ‘The Big

Partridge.’”.

Grifftihs 129:7 (1886, reissued 1895)

Dr. Gilfillan then gives a detailed analysis of the contents of the service book, as published in 1895, and continues:

“In the new parts of the 1895 edition we did not take Dr. O’Meara’s translation as a basis, but translated directly from the English. Many new selections of Psalms and new Occasional Prayers were thus translated. Of the hymns in this edition many were taken from a collection of Ojibway Hymns, edited by the Rev. John Jacobs and others, of Walpole Island, Canada . . .”

In the 1895 edition Dr. Gilfillan was assisted by the Rev. George B. Morgan, a born Chippewa, and by his brother, a layman.

Dr. Gilfillan was born October 23, 1838. He graduated from the General Theological Seminary, New York, in 1869. From 1869 until 1873 he was rector successively of two English churches in Minnesota. From June, 1873, until, September, 1908, he served as missionary to the Ojibways at White Earth, Minnesota. He retired in 1908 and is now living in Washington, D.C. Dr. Gilfillan, in agreement with many other missionaries to the Indians states that:

“As for the Christian Indians they are excellent people, and there were everywhere among the Christians, saints. The best people and the best Christians I have ever known were Indian Christians.”

Dr. Gilfillan has had the superintendence of all the missionary work

of the American Episcopal Church among the Chippewa in Minnesota; his

circuit covering an area of nearly three hundred miles in the northern,

sparsely inhabited region of the State, and including eight Indian churches,

presided over by eight full-blood Chippewa clergymen. Nine full·blood

Indian clergymen were trained and presented for ordination by him. In

the fall of 1888 he built four boarding schools — one at Wild Rice River,

another at Pine Point, the third at Leech Lake, and the fourth at Cass

Lake.

[3] Warren was a lineal descendant of the brother of General Warren, of Bunker Hill fame. His grandfather came from New England as a fur-trader and married an Ojibway woman.

[4] Beaulieu was also a mixed-blood of the famous French family of the

Leroy-Beaulieus. He was a very eloquent man, with a great gift of language.

Most of the half-breeds on the Reservation were descendants of French

voyageurs and fur-traders.

The latest Chippewa translation of the American Prayer Book appeared in 1911, entitled: .

* Iu Wejibuewisi | Mamawi Anamiawini | Mazinaigun. | Tibishkejoi abajito | Ima Shaganoshshi Anamiawini. | Gaye tigosi pugi | Wawenabujiganun iniu Nugamowinun au David. | New York. | The New York Bible and Common Prayer Book Society. | 1911. |

280 pages. Paper, 3⅝ x 5½ inches. Title, reverse blank; text, pp. 3-280. P. 3 contains an explanatory note concerning the dash beneath letters which has the force of “ng.” P. 4, blank; p. 5 has the certificate of the bishop, etc. The Prayer Book extends from pp. 7-212, printed in long lines. Headings, subheadings, running headlines and rubrics are in English only. Contents: Morning Prayer, pp. 7-24; Evening Prayer, 25-38; Litany, 39-49; Prayers and Thanksgivings, 50-58; Collects, Epistles and Gospels, 59-102; Holy Communion, 103-129; Baptism of Infants, 130-146; Baptism to such as are of Riper Years, 147-158 ; Catechism, 159-166; Confirmation, 167-171; Matrimony, 172-177; Communion of the Sick, 178-179; Burial, 180-188; Prayer and Thanksgiving for Harvest, 189-191; selections of Psalms, 192-204; Family Prayers, 205-212. Pp. 213-280 contain Ojibwa Hymnal, compiled by Rev. Edward C. Kah-O-Sed . . . 1910. Title, p. 213; 214 blank; 68 hymns and doxology, pp. 215-276. Pp. 276-280 English index and Ojibwa index of hymns.

The translator and editor of this edition, the Rev. Edward Coley Kah-O-Sed, was born on Walpole Island, Ontario, Canada, September 30, 1870, the son of Christian parents. In 1894 he came to Minnesota as an interpreter for a missionary at Red Lake, Indian Reservation. In 1896 he went to Seabury Hall, Faribault, Minnesota, and graduated there in 1900. Since 1905 he has been stationed at Beaulieu, Minnesota. He was ordained priest in 1907 by the Right Rev. James Dow Morrison, bishop of Duluth. The 1895 edition of Dr. Gilfillan, having been exhausted by this time, Mr. Kah-O-Sed prepared the edition, just described[5].

Griffiths 129:9

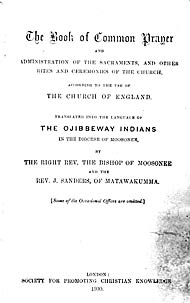

Another translation of the English Liturgy for the benefit of Chippewa Indians in Canada remains to be mentioned. In 1880, and again in 1881, the S.P.C.K. published the Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments. . . . Translated into the language of the Ojibbeway Indians in the Diocese of Moosonee, by the Right Rev. the Bishop of Moosonee and the Rev. J. Sanders, of Matawakumma. (Some of the occasional offices are omitted) . . . 152 pages. Paper, 4 x 6½ inches. Title, reverse printer’s name; text, pp. 3-152, entirely in the Chippewa language and in syllabic characters.

Of the bishop of Moosonee, the Right Rev. John Horden we shall learn more in Chap. LXVIII. His collaborator, the Rev. John Sanders, was an Indian clergyman in Bishop Horden’s diocese.

CHAPTER LXVIII

THE ALGONQUIAN FAMILY, II

BY a strange chance, if chance it may be called, no schooling was required to make religious books intelligible to a great number of Indians. About the year 1824 Sequoyah (George Guest, Giss, Guess, 1760-1843)[1], a Cherokee, who had often heard of “the talking leaf” of the pale faces, contrived a syllabic system of eighty-five characters, which superseded the old birch-bark picture-writing of the red man. He analysed the sounds of his intricate polysynthetic tongue, and provided symbols for a complete syllabic system by various ingenious modifications of the capital letters of an English primer. This idea was adopted and developed in 1841 by-the zealous Wesleyan missionary, James Evans (1801-46), labouring in the Hudson’s Bay region. In a few years-the Indians teaching each other-his phonetic syllabary of dots, dashes, curves, hooks and triangles became a written language among the tribes between the Hudson’s Bay and the Rocky Mountains[2].

[2] Canton, Vol. IV, p. 174; and John McLean, James Evans: Inventor of the Syllabic System of the Cree Indians; Toronto; Methodist Mission Rooms; 1890; 208 pp.; 8vo. “Evans whittled out his first types for patterns, and then, using the lead furnished him by the Hudson Bay company’s empty tea-chests, he cast others in moulds of his own devising. He made his first ink out of the soot of the chimneys. His first paper was birch-bark, and his press was also the result of his handiwork.”

The first of these syllabic systems, the. still existing “Micmac hieroglyphics,” so-called, was the work of Pere Chrestien Le Clercq (1630-1695) in 1665 ; improved by Father Christian Kauder in 1866. One of the most recent is the adaptation of the “Cree syllabary” of Evans by the Rev. Edmund James Peck to the language of the Eskimo of Cumberland Sound [see below, Chap. LXXIV]. The basis of many of the existing syllabaries is the Evans syllabary. This syllabary and modifications of it are now in use for both writing and printing, among many tribes of the Algonquian, Athaab(p)ascan (modified by Father Adrien Gabriel Morice for the Dimes or Tinnes, by Kirkby and others for Chipewyan, Slave, etc.), Eskimo (modified by Peck) and Siouan stocks. The most remarkable of all these syllabic alphabets is the well-known Cherokee alphabet of Sequoyah. This alphabet was first used for printing in 1827. and it has been in constant use since then for correspondence and for various literary purposes. Sequoyah’s invention finds its parallel in the construction of the Vai alphabet by Doalu Bukere at Bandakoro, Liberia, so graphically described by Sir Harry Johnston in his Liberia, Vol. II (1906), pp. 1,107-1,135.

[1] See Handbook of American Indians, Vol. II, pp. 510, 511.

It is this system in which Bishop Horden’s Chippewa book, mentioned in the preceding chapter, and most of the following translations of the Prayer Book are printed.

The Crees are the largest and most important Indian tribe in Canada.

They are, as mentioned in Chapter LXVII, a part of the great Algonquian

stock, and are closely related to their southern neighbours, the Chippewa

(Ojibway). With both French and English they have generally been on friendly

terms. The earliest missionaries in the Cree country — as in all missionary

territories — were the Roman Catholics. Here it was the French Jesuits,

who accompanied the French commander Pierre Gaultier de La Verendrye,

Sieur de Varennes, in his explorations of the Saskatchewan and the Upper

Missouri rivers from 1731 to 1742.

There are in Cree three dialects: (1) the Eastern or Swampy Cree, spoken in the lower Saskatchewan Valley; (2) Moose, a variety of Eastern Cree, spoken by a small number of Indians near Moose Fort, Hudson’s Bay; (3) Western or Plain Cree, spoken from the shore of Hudson’s Bay to Lake Winnipeg, and then westward along the Saskatchewan river to the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

Protestant work among the Cree Indians was begun in 1820 by the Rev. John West (1778-1845), an Episcopalian minister, and chaplain for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Garry (Winnipeg) on Red river. For many years the Crees had lived then in the region called Prince Rupert’s Land, the Canadian territory lying around Hudson’s Bay ..

In August, 1844, the Rev. James Hunter, later archdeacon of Cumberland,

Rupert’s Land, began his missionary labours among the Crees at

York Fort, Devon Station, Cumberland. He was born April 25, 1817, in

Barnstaple, Devonshire, England, where he also acquired his education.

He soon became to the Indians one of the beloved “white praying

fathers.” From 1855 to 1865 he lived at Winnipeg as rector of St.

Andrew’s Church. Most of his translations were done at Devon Station,

where he was assisted not only by his wife but also by Henry Budd, the

earliest convert of the Rev. John West and the first native pastor of

the Cree Mission. Returning to England in 1865, Hunter was appointed

vicar of St. Matthew, Bayswater, London, where he worked for many years

most successfully as a ·preacher and organiser. He died there

on February 12, 1881. Of great assistance to him was his wife, Jean,

nee Ross, an able linguist and capable translator.

In 1859 Hunter had published the whole Liturgy in syllabic characters, excepting the title-page, which reads [One line of syllabic characters: Ayumehawe Mussinahikun]. The Book of Common Prayer, . . . Translated into the language of the Cree Indians of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land, North-West America. [“Archdeacon Hunter’s translation.”] London: Printed for the S.P.C.K. . . . 1859.

Title, reverse blank; explanation of the Syllabary, signed W[illiam]

M[ason]; reverse blank. Text entirely in the Cree language, syllabic

characters, 190 pages. Paper, 4 x 6½ inches. The transliteration

into the Cree syllabary was made by the Rev. William Mason, of the C.M.S.

The edition has often been reprinted, apparently without any change.

It does not include the Psalms of David.

In 1876, and again in 1877, the S.P.C.K. published editions of the Liturgy in Cree, roman characters. The one has an English title, excepting the first line; the second a title in Cree, reading: Ayumehawe Mussinảhikum, | mena | kā isse Mākinanewửkee | Kunache Kẻche Issẻtwawina, | mena | ateẻt kotuka issẻtwawina ayumehawinỉk, | ka isse aputchẻtanewukee | akayasewe ayumehawinỉk: | ussitche | David’ oo Nikumoona, | kā isse nikumoonanewủkee ảpo kā isse ayumetanewủkee | ayumehāwekumikoỏk. | Ā isse Mussinảhủk nāheyowe isse keeswā- | winỉk, akayasewe mussinảhikunỉk ỏche, | the Ven. Archdeacon Hunter, D.D. | (late Archdeacon of Cumberland, Rupert’s Land), | Vicar of St. Matthew, Bayswater, London. | [London:] . . . | 1877, iv, 739 pages. Paper, 4 x 6¾ inches.

A literal translation of this title as given in Pilling, reads: Prayer Book, | and | as they-shall be-given | holy great Sacraments, | and | other. lesser ordinances in-religion, | as they-shall be-used | English worship-in: | Also | David’s Psalms, | as they-shall be-sung or shall be-read | in-the-church. | As he-has written the-Cree lan- | guage-in, the-English service-book from, | the Ven. Archdeacon Hunter | ·etc. Pp. 1-67 contain the same matter, nearly page for page and line for line, as the ed~tion of 1855, but the type is not the same. Pp. 469-739 contain the Book of Psalms.

Archdeacon Hunter’s work was, primarily, for the benefit of the Swampy Crees. The territory of the Western or Plain Crees was taken care of, mostly, by the Wesleyan Missionary Society. The middle section, the Moose Cree Indians, were ministered unto mainly by John Horden, the apostle of the Hudson’s Bay shore .. The Indians here numbered, all told, about one thousand. Horden, the son of a printer, was born at Exeter, Devonshire, England, in 1828, and died in 1893. He left England in 1851, at the direction of the C.M.S., to work as a lay missionary in an extremely remote corner of Rupert’s Land. Soon afterwards he was appointed missionary to the Cree and Ojibwa Indians, with station at Moose Fort, North-Western Canada. In 1852 Bishop David Anderson visited Moose Fort and ordained Horden deacon and priest. When Rupert’s Land. was divided, in 1872, into the four dioceses: Rupert’s Land, Moosonee, Saskatchewan, and Athab(p)asca, Horden was consecrated in Westminster Abbey the first bishop of Moosonee — the Indian word for Fort Moose — on December 15, 1872. When death carne to him at Moose, January 12, 1893, he was engaged in revising his own translations and .Dr. William Mason’s Cree Bible. His literary work consists of translations of the Bible, Prayer Book, hymns and Gospel history into the Cree language;, several translations into. Saulto, the language of the Saulteux Indians — a dialect of the Chippewa language; into Eskimo, and into Chippewa proper, and other minor translations. “He was always. one of my heroic people,” said Archbishop Tait of him.

In 1852 Horden had set about translating a part of the English Prayer

Book. He sent the manuscript to the C.M.S. in London with the request

that it might be printed, and copies sent to him by the next annual ship.

Instead of printing the book, the society sent a printing press and types,

with a good supply of paper, together with book-binding material, of

the use of which Horden knew absolutely nothing. He determined to do

his best, however, and by the spring of 1854 he issued “A portion

of the Book of Common Prayer in the Cree language.” Moose Factory,

Hudson Bay, 1854.

Five years later, in 1859, W. M. Watts, London, printed for the C.M.S.: The Book of Common Prayer. ... Translated into the language of the Moose Indians of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land, North-West America. (“Rev. J. Horden’s translation”) (2), 361 pages, 16mo. Text entirely in the Moose dialect, and printed in syllabic characters.

Soon after his arrival at Moose Fort Horden taught the Indians to read

according to the syllabic system invented by Evans, which is easily

acquired. In this system he printed and had printed editions

of the Prayer Book, hymnals, the four Gospels, and other literature for

religious instruction.

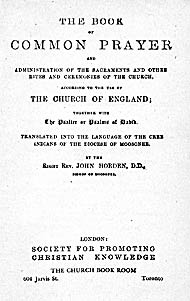

In 1889 appeared: The Book of Common Prayer, . . . Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David. Translated into the language of the Cree Indians of the Diocese of Moosonee. By the Right Rev. John Horden, D.D., Bishop of Moosonee. . . . (Printed with the approval of the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury). London: S.P.C.R. . . . 1889. (3), 298; (2), 188 pages. Text entirely in the Cree language, and in syllabic characters. The Psalter has a special title-page and separate pagination. This edition omits the introductory material of the English Book (Nos. 1-8), and also Nos. 26-29, i.e. Forms of Prayer to be Used at Sea, the Ordinal, The Form of Prayer for the 20th of June, and the Articles of Religion.

Archdeacon Kirkby’s work for the benefit of the Cree Indians will be mentioned in Chapter LXXI.

For the use of the Saulteux Indians Horden published: The Morning and Evening Services, according to the use of the United Church of England and Ireland. Translated into the language of the Saulteux Indians of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land, North America. By the Rev. John Horden, Missionary of the Church Missionary Society, Moose. [London: W. M. Watts, . . . ], 1861. Title, reverse printer’s name; text, pp. 3-36, in the Saulteux dialect of the Chippewa language, syllabic characters, except an English heading, “The Nicene Creed,” p. 35, 16mo.

Griffiths 22:3; reprinted many times.

Cree Book of Common Prayer

(Griffiths 22:3, 1949 printing)

CHAPTER LXIX

THE ALGONQUIAN FAMILY, III

THE Mikmak (Micmac) was formerly the principal

Indian language in Nova Scotia. The Micmacs or Souriquois Indians dwelt

in Prince Edward Island and along the adjoining coasts of Cape Breton,

Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. Few of them had any knowledge of English,

nearly all were Romanists, and very illiterate. We are told by Tucker, The

English Church in Other Lands (1886), p. 28, that toward the second

half of the eighteenth century “the Micmac, Marashite, and Caribboo tribes

of Indians were powerful and numerous, and for their instruction portions

of the Prayer Book and Bible were translated into their language.” As

a matter of fact, portions of the Prayer Book, translated by the Rev.

Thomas Wood between 1766 and 1768, were forwarded to the S.P.G., whose

receipt of them is found acknowledged in the society’s report for

1767. The manuscript was never printed. Wood was the S.P.G’s missionary

in New Jersey, stationed at Elizabethtown, and New Brunswick, from 1749

to 1752. He was then transferred to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and remained

there until 1763[1]. From 1763 until 1778 he ministered to

congregations at Annapolis (formerly Port Royal) and Granville, N S.

He died December 14, 1778. Immediately upon his arrival at Annapolis

Wood applied himself to the study of the Micmac language, and officiated

in it publicly in July, 1767, in St. Paul’s Church,

Halifax. In 1769 Wood spoke of “the Micmacs, Marashites [Malecite,

Maliseet], and Carribous, the three tribes of New Brunswick,” as

all understanding the Micmac language[2]. The last-mentioned tribe are

very probably the Abnaki, or a part of them. as one of their gentes is

the Magunleboo, or Caribou.

The Rev. Richard Flood was a S.P.G. missionary at the new mission established

among the Munsee (Munsey) or Delaware Indians at Caradoc, on the Thames

River, Ontario, from 1834 until 1846, and at the Indian mission of Munsee

Town, twelve miles from Delaware, Ontario, from 1841 to 1855. The majority

of the Indians at the mission were Munsees,. a branch of the Delaware nation

who had come into Canada to assist the British against the American colonies.

They were a remnant of those Delaware refugees from the United States,

who for many years during the colonial period had been the object of Moravian

care. During the eighties of the last century they lived in three villages:

Munsee Town, Moravian Town, and Grand River, in the province of Ontario,

Canada. Flood’s first convert was the leading chief of the tribe,

Captain Snake, who was baptized in 1838. Flood’s ministrations extended

also to the Potawatomies, the Oneidas and the Chippewas in the neighbourhood[3].

[l] See further, Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit, Vol. V. pp. 328, 329. Digest of the S.P.G. Records, Fifth Edition, 1895. pp. 112-113, 125-126. The account of Wood’s relations to the dying abbot Maillard as given in Sprague and in the Digest are stoutly contradicted in The Catholic Encyclopædia, Vol. IX, p. 539. Antoine Simon Maillard, the apostle of the Micmacs, was a missionary to the Indians in Arcadia from 1735 until his death, August 12, 1762. He was also vicar-general to the bishop of Quebec from 1740 on. He was the first to acquire a complete mastery of the extremely difficult language of the Micmacs, for whom he composed a hieroglyphic alphabet, a grammar, a dictionary, a prayer book, a catechism, and a series of sermons. A careful examination of the literary remains of Maillard and of Wood leaves no doubt as to the fact that the latter made most ample use of the former’s papers of which he took charge after the abbe’s funeral.

[2] Hawkins, Missions, 1845, p. 361.

[3] An interesting account of a visit to this mission is

contained in James Beaven, Recreations of a Long Vacation, etc. (1846),

pp. 68-82.

A later edition, containing on pp. 8-163 an exact reprint in slightly larger type of pp. 2-157 of Flood’s translation, page for page and line for line, together with a large number of hymns, was put out by the S.P.C.K. in 1886, entitled:

* Morning and Evening Prayer, the Administration of the Sacraments, and certain other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church of England; Together wit:p. Hynms. [Munsee and English] Translated into Munsee by J. B. Wampum, assisted by H. C. Hogg, Schoolmaster. [This translation is not free from imperfections, but since it has been many years in use, and there are hindrances to its immediate revision, the Archbishop of Canterbury gives his Imprimatur to this edition for present use.] London: S.P.C.K. [1886]. Colophon: Oxford: | printed by Horace Hart, printer to the University.

Title, reverse blank; preface (signed John Wampum, or Chief Wau-bun-o), pp. iii, iv; contents, p. (5), reverse blank; half-title, p. 7; text, pp. 8-349; colophon, p. (350) ; l6mo. The hymns in Munsee occupy pp. 165-171; hymns , in English and Munsee, pp. 172-349. Most of the hymns were translated by Charles Halfmoon, a local native preacher. Some were by the Rev. Abraham Luckenbach (1777-1854), “the last of the Moravian Lenapists,” who ministered to his Munsee and Delaware flock on the White river, and later on the Canada reservation, from 1800 to the day of his death in 1854. With him died out the traditions of native philology (Brinton).

[4] This is the “Caribou” language, mentioned above.

[5] According to Brinton, Lenape and Their Legends, p. 74, the Barbaro-Virgineorum dialect was the Delaware as then current on the lower Delaware river. The Mahakuassica was the dialect of the Susquehannocks or Minquas who frequently visited the Swedish settlements.

The Catechism is a paraphrase rather than a literal translation. Each paragraph of the Delaware version is followed by the Swedish “versio,” and that again by the text of Luther in Swedish, this last in larger type.

The author, Johan Campanius Holm, was born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1601, and died there September 17, 1683. He was a missionary at and near Fort Christina (Newcastle) on the Delaware, from 1643 to 1648, when his labours in New Sweden ended. Shortly after his arrival at Christina he was transferred to Upland, where he settled with his family and conducted the service at New Gothenborg, built by Governor Johan Printz. Campanius was the most important and the best known of the early Swedish preachers on the Delaware. He worked hard and diligently. He manifested a deep interest in the welfare of the Indians, and applied himself to learning their language. They often came to listen to his sermons in silent wonder. In his translation of Luther’s Smaller Catechism Campanius was assisted by Jacob Swensson, Gregorius van Dyck, and Hendrick Huygen, commissioner for the colony. The translation was probably ready in its first draft in 1648, when Campanius returned to Sweden. It was revised there, and in 1656 sent to the king for publication, together with a memorial. It was not printed, however, until 1696. The book to-day is of great rarity, only a few copies of which are known to exist.

The Ottawa are a tribe of North American Indians of Algonquian stock, originally settled on the Ottawa river, Canada, and later on the north shore of the upper peninsula of Michigan. They were driven in 1650 by the Iroquois beyond the Mississippi, only to be forced back by the Dakotas. Then they settled on Manitoulin Island, Lake Huron, and joined the French against the English. During the War of Independence, however, they fought for the latter. Some were moved in later years to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), but the majority live to-day in scattered communities throughout Lower Michigan and Ontario.

It was for the Ottawas of Lower Michigan that the Rev. George Johnston,

a missionary of the Protestant Episcopal Church, published: The

Morning and Evening Prayer, translated from the Book of Common Prayer of the

Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, together

with a selection of Hymns. Detroit: Geiger and Christian, Printers. 1844.

Griffiths lists no texts in Ottawa.

Title (also printed on the cover), reverse containing the approval of Samuel A. McCoskry, bishop of Michigan. Text, pp. 1-59, containing: Prayers in Ottawa, with English headings, pp. 1-25; 26, Letter (in English) from George Johnston to Bishop McCoskry, dated Grand Traverse Bay, January 1, 1844, transmitting the translation; the Ten Commandments, pp. 27-28; p. 29 blank. Pp. 30-59, Hymns, alternate English and Ottawa. The translator used the English alphabet in its ordinary and natural manner, as known to English readers. The translation is used at the Griswold Mission in Western Michigan.

The Rev. F. A. O’Meara, in Second Report of a Mission to the Ottahwahs and Ojibwas on Lake Huron, London, 1847, p. 28, criticizes the book rather severely:

"Though on the title-page it professes to be a translation of the Morning and Evening Services, it contains only the Morning Service, the Litany, and the Ten Commandments, to which are added a few hymns taken word for word from Peter Jones’s collections. On looking over the work, I find it very carelessly done, and in many places a total misrepresentation of the spirit and meaning of the Liturgy .... The Absolution is also made a prayer, or rather an unintelligible mixture of prayer and exhortation. . . .”

The Cheyenne are an important plains tribe of the great Algonquian family. They are divided into Northern and Southern. The Southern Cheyenne were assigned to a reservation in Western Oklahoma by treaty of 1867, but they refused to remain upon it until after the surrender of 1875. In 1892 the lands of the Southern Cheyenne were allotted in severalty, and the Indians are now American citizens.

In 1900 a Cheyenne Service Book was published, entitled: Cheyenne Service

Book. Compiled by Rev. D. A. Sanford, Shawnee, Okla. Churchman Press.

1900. 20 pages, without special title-page, the title on the cover. Printed

in long lines. Paper, 5½ x 7¾ inches. Pp. 11 (med.) to

17 (end) contain hymns; pp. 18-20 Cheyenne words with English translation.

Griffiths lists no texts in Cheyenne

The author, David Augustus Sanford, graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1875, and from the Philadelphia Divinity School in 1878. He served as a missionary to the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians at Bridgeport, Okla., from 1894-1907. His experiences as a missionary he has published in 1911, entitled Indian Topics; or, Experiences in Indian Missions, with selections from various sources. New York. In his translation Mr. Sanford had the help of several Indians, viz., the Rev. David Pendleton Oakerhater, missionary at Etna, Okla., and the late Luke Bearshield[7].

The Arapaho are another important tribe of the Algonquian family, closely

associated with the Cheyenne for at least a century past. The name Arapaho

may possibly be, as Jno. B. Dunbar suggests, from the Pawnee tirapihu

or larapihu, “trader”[8]. By the treaty of Medicine

Lodge in 1867 the Southern Arapaho, together with the Southern Cheyenne,

were placed upon a reservation in Oklahoma, which was thrown open to

white settlement in 1892, the Indians at the same time receiving allotments

in severalty, with the right of American citizenship.

[7] I am indebted to Mr. Sanford for information concerning the translation and the translators of the Cheyenne Service Book.

[8] Dunbar, Jno. B., “The Pawnee Indians” in Magazine of American History, Vols. IV, V, VIII; Morrisania, N.Y., 1880-82.

A Northern Arapaho, Fremont Arthur, deceased, compiled, some years ago, a little book of Questions and Answers, a sort of Catechism, in both English and Arapahoe. It contains from the Prayer Book: the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Creed, with the answer, following the Creed, in the Catechism. The American Bible Society published a translation of the Gospel according to Saint Luke. New York, 1903. The translation was made by the Rev. John Roberts, of the Shoshone Mission of the Protestant Episcopal Church to the Shoshone and Arapaho Indians, Wyoming.

The greater part of the Prayer Book has been translated by Roberts; with the assistance of the Rev. Sherman Coolidge, a full-blood Arapaho Indian; but it has not yet been printed.

Griffiths lists no texts in Arapaho.

A shortened form of Morning Prayer, with the Ten Commandments, translated into Arapaho by the Rev. Roberts, is available online.