PART THE FIFTH

AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC OCEAN

CHAPTER XLII

INTRODUCTORY-AUSTRALIA

ACCORDING to Codrington and Palmer[1], the languages of the Ocean family fall naturally into place in four geographical areas: Indonesia, Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia. (1) The Indonesian group includes the language of Madagascar, with those of the Malay archipelago. The principal members of it are Malagasy, Malay, the various languages of the Philippine Islands, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Celebes, and of the islands eastward towards New Guinea. (2) The Micronesian group takes in the Caroline Islands, the Pellew, Marshall and Gilbert Islands. (3) The Melanesian languages are those spoken by the present inhabitants of the great chain of islands which extends from the east of New Guinea to New Caledonia, including Fiji. (4) The Polynesian languages of the Eastern Pacific are well known as those of Samoa, Tonga, Hawaii and the Maori of New Zealand.

Purely for geographical reasons the Malagasy translations will be treated in Part VI, Chapter L, while Borneo, the Dyaks, etc., have been discussed in Part IV, Chapters XXXVIII and XXXIX.

No translations of the Liturgy or of portions thereof are known to us for the islands of the second group.

Concerning the peoples of groups (3) and (4) George Brown, Melanesians and Polynesians, pp. 15 foil., states that

“The Melanesian and Polynesian peoples were descended from one common stock, of which the Melanesian is the oldest representative at the present time. . . . Their languages do not belong to the Indo-European, but to the Turanian family, though the language has from time to time been very much modified by admixture with forms of speech brought in by repeated immigration from Aryan-speaking races on the mainland of India. . . . The original inhabitants were Negritos . . . speaking a more or less agglutinative tongue. Their original home was in India, probably in the valley of the Ganges.”

Sidney H. Ray, we notice, arrives at somewhat different conclusions.

For the aborigines of Australia proper not much has ever been done by

any Christian church body in the way of translating the Scriptures or

a liturgy into their native tongue. The Australian Blacks, or New Hollanders,

as they were called, wretched and miserable, were made so even more by

the contact with the white settlers. Their immediate homes taken away

from them by force or by stealth, they were in many cases forced back

into the waterless desert, or, as in Tasmania, blotted out as a people.

The work of the C.M.S. among the Australian Blacks, begun in 1825, is

graphically described by Eugene Stock in Vol. I, pp. 360, 361, of his

centennial history. The missionary efforts centred at Wellington Valley

and Moreton Bay, but were given up in 1842, owing to difficulties with

which the missionaries had nothing to do. The C.M.S. missionary, the

Rev. James Günther, made at least a beginning in linguistic and translational

work for the benefit of his coloured flock. A vocabulary and a grammar

were prepared and published, and translations of three Gospels, portions

of Genesis and the Book of Acts, and a large part of the Prayer Book,

were made and printed for the use of the natives[2].

[1] A Dictionary of the Language

of Mota, Sugarloaf Island, Banks’ Islands. With a short grammar and

index. London, 1896. Preface, p. xv.

Griffiths records no translations for the Australian Aborigines

A new beginning was made in 1850 by the Anglican Board of Missions for Australia and Tasmania, and now each diocese is responsible for its own area[4]. Most of the blacks are at present in the north-western part of Australia, and it is to be hoped sincerely that the election of the well-known missionary, Bishop Gerard Tozer, in 1910, formerly (1902-10) bishop of Nyasaland, Africa, to the see of North-West Australia will bring about a flourishing mission among these Australian aborigines[5]. The new bishop is no stranger to the Australian Church, for he has been in earlier years incumbent of Christ Church, Sydney. The neglect in recent years of the work of the Church of England among the aborigines of Australia and other continents is regretfully acknowledged by Bishop Gilbert White, of Carpentaria, in the S.P.G. Report for 1901, pp. 169, 170.

[3] These biographical data have been kindly furnished by Mr. Günther's son, Archdeacon Günther, of Paramatta, now at North Sydney.

[4] See, further, Wynne, pp. 110 foll., and N. W. Thomas, Natives of Australia, p. 216.

[5] S.P.G. Report, 1911, pp. 207, 208. On the work among the aborigines

of Australia see also The Guardian, May 30, 1913, p. 686, cols. 2, 3.

CHAPTER XLIII

THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS

THE Bontoc Igórot have their centre in the pueblo of Bontoc, Luzon, Philippine Islands. Bontoc, the capital of the sub-province Bontoc, is situated in the narrow valley of the Rio Chico, in the mountainous interior of North Luzon. The word Bontoc-pronounced “Ban-tâk “-is a Spanish corruption of the Igórot name, “Fun-tâk,” a native word for mountain, the original name of the pueblo.

“In the matter of religion and spirit-belief,” writes Albert Ernest Jenks, on p. 39 of The Bontoc Igórot (1905), “the surface has scarcely been scratched. The only Igorot who became Christians were the wives of some of the Christian natives, who came in with the Spaniard, mainly as soldiers.”

Since the annexation of the islands to the United States, however, the number of converts to Christianity has increased markedly among the 13,582 civilised Igórot, while very few can be found among the wild population, numbering nearly 198,000.

The language of the Bontoc Igórot is sufficiently distinct from

all others to be classed as a separate dialect. It descends originally

from a parent stock which to-day survives more or less noticeably over

probably a much larger part of the surface of the globe than the

tongue of any other primitive people. The language of every group of

primitive people in the Philippine archipelago, except the Negrito, is

from that same old tongue. The Malay language of the Malay Peninsula,

of Java, and of Sumatra, belongs here. So do many, perhaps all, the languages

of Borneo, Celebes and New Zealand. This same primitive tongue is spread

across the Pacific Ocean, and shows unmistakably in Fiji, New Hebrides,

Samoa and Hawaii, as well as in Madagascar.

not listed by Griffiths

The Tagálog, numbering about one and a half million, belong to the seven Christian tribes[1] which constitute the great bulk of the population of the Philippine Islands. The Tagalog are the chief population of Manila and central Luzon and the majority of the inhabitants of Mindanao. They are the most cultured of the brown races in the Philippines. A Tagálog Communion Office was published in 1906, reading: Ang orden | Nang Pangangasiwa ng | Hapunan ng Panginoon | O’ santong Pakina- | bang (ang Misa). | Manila. | Imprenta de Fajarado y Compo. . . . | Reverse of title blank; text, pp. 1-26. Small 8vo. No running headlines; text, sub-headings, rubrics, etc., in Tagalog. Printed in long lines.

In a letter dated July 18, 1912, Bishop

Brent, of the Philippine Islands,

writes:

[1] The seven Christian tribes are: The Visayan, Tagalog, Ilocano, Bicol, Pangasinan, Pampangan, and Cagayan.

no Tagalog translation is listed by Griffiths, although we do have a Tagalog translation of Holy Communion from the 1979 BCP.

“The translator of the Tagalog Communion Office is the Rev. George Charles Bartter, who came to the Philippine Islands at the beginning of American occupation as an agent of the British and Foreign Bible Society[2]. He was at that time a young man of about twenty-two. He acquired several of the dialects and did excellent work in the position he occupied. Later on I proposed to him to consider the desirability of entering Holy Orders. He was ordained Deacon in 1907, and Priest in 1909. He is in charge of St. Luke’s chapel, a Filipino work in the city of Manila. He is planning the translation of further portions of the Prayer Book, into Tagalog.

“The only other translations thus far made, in addition to the Tagalog and Igórot which you have, are portions of the Prayer Book into Ilocano, done in the Mission of St. Mary the Virgin, Sagada. These have not yet been published, but I hope before very long we shall have sufficient to warrant going to press.”

The men in charge of St. Mary the Virgin, Sagada, are the Rev. John Armitage Staunton, Jr., and the Rev. Robert Tarrant McCutcheon.

The Ilocanos belong to the seven Christian tribes among the Philippines. The majority of them are living on the shore-slopes of the western half of North Luzon. Centuries of living in the least fertile portion of the archipelago have made them a thrifty and industrious race. They are the Yankees of the Philippines, and by virtue of their industry the population has increased to such an extent that they have migrated throughout the islands.

“There are, perhaps, no more industrious workers than the llocanos of the populous northwest coast of Luzon, or the Igorotes who have built stupendous rice-terraces in the mountainous heart -of that island.” — WRIGHT.

[2] See, also, Canton, Vol. V, pp. 156, 157.

CHAPTER XLIV

THE NEW GUINEA MISSION

NEW GUINEA is the largest island in the world, except Australia. It

is divided politically between Great Britain, Germany and Holland. Ethnologically

the natives belong as a whole to the Melanesian division of the Indo-Pacific

races. The predominant tribe are the Papuans[1]. In :some of the Kei

and Aru islands the Papuan inhabitants form orderly Christian communities.

The part of New Guinea assigned to Great Britain is known now as the

Territory of Papua. It may be that from an indigenous Negrito stock of

the Indian archipelago both, Negroes and Papuans, sprang, and that the

latter are an original cross between the Negrito and the immigrating

Caucasian who passed eastward to found the great Polynesian race.

[1] Malay papúwah, or puwah puwah, “frizzled,” “woolly-haired,” in reference to their characteristic hairdressing.

The Papuan languages or dialects are very numerous, owing doubtless to the perpetual inter-tribal hostility which has fostered isolation. Several dialects are sometimes found on one and the same island.

In the south-eastern portion of New Guinea, possessed by Great Britain, the London Missionary Society (1871), the Australian Wesleyans (1892), and the Anglican Church of Australia (1892), have arranged a friendly division of the field and have met with gratifying success. The history of mission work here is one of exploration and peril amongst savage peoples, multitudinous languages, and an adverse climate, but it has been marked by wise methods as wen as enthusiastic devotion, industrial work being one of the basal principles.

In his interesting treatise, British New Guinea, Country and People (1897), Sir William MacGregor, then lieutenant-governor of British New Guinea — now governor of Queensland — states on p. 90:

“The Anglican Mission is understood to have as its field of operations the whole of the north-east coast from East Cape to the British-German boundary. It was opened in 1891 by the late Rev. Albert MacLaren. He was an enthusiastic missionary, possessed of much originality, and capable of feeling with natives the sincere sympathy that alone ever enables a man to obtain their full confidence. His death, a few months afterwards, was a blow from which the mission never recovered. The Rev. Copland King has done all he could do under such circumstances, left as he has been without a staff, although provided with accommodation for it and with means of transport. The result has been that, in spite of the· honourable efforts of the devoted Mr. King, this young and tender offshoot of the great National Church has been left hopelessly behind the other missions. There is reason to believe that this fact is now being recognized in the proper quarter, and that Mr. King will receive the assistance he should have had long ago.”

And on p. 93, the author continues:

"The Anglican Mission must really take up work in earnest and become greatly extended.”

That this reproof of an able statesman no longer applies to the present condition of affairs in British New Guinea is a matter of record. The mission has become a diocese, with a bishop and an efficient mission staff. The Liturgy has been, in part, translated into some of the dialects of the land, and others will undoubtedly soon follow.

Of the two faithful early workers mentioned by Sir William, we would say here that the Rev. Albert Alexander MacLaren was born in 1853. He became the first S.P.G. missionary to New Guinea, pioneering there since 1891, and dying of fever at sea on board the “Merrie England,” December 28 of the same year. The Rev. Copland King, the colleague selected by MacLaren when the latter began his work, has been for years one of the most faithful missionaries in New Guinea. He graduated B.A. from the University of Sydney 1885; M.A. 1887; was ordered deacon 1886, and ordained priest 1887, by the bishop of Sydney. Since 1891 he has been missionary priest of the diocese of New Guinea, and until the appointment of the first missionary bishop, the Right Rev. Montagu John Shaw Whigg in 1898, he was head of the New Guinea Mission. Since then he has been stationed in several places, at present at Ambasi, Northern Division, Papua.

King has made Wedau his special study, publishing in the first place a Wedau grammar. The Wedau is one of the Melanesian languages of New Guinea spoken on the west shore of Bartle Bay.

“In school, and at most of the church services,” says Chignell, on p. 21 of his recent book, An Outpost in Papua (1911), “we have to use Wedauan, the nearest that the Mission has to a lingua franca. Wedau is a village at the foot of Dogura Hill, and the language of the people living there is, perhaps, the only New Guinea language that the Anglican Missionaries have completely explored. Into it the Book of Common Prayer and the entire Lectionary, and about a hundred hymns, have been translated.

The lectionary referred to is an Old Testament Lectionary:

Ezra-Malachi, and the Apocrypha, 407 pages (1910), translated by Annie

Ker. There has been published also an illustrated Story of the Gospels,

and a Reading Book. In 1895 there was printed at Sydney a primer, containing

prayers, Psalms i, xxiii and c, the Decalogue, hymns and a catechism,

12 pages. Its title reads: Pari Salamo Ieova Riwana. Wela. Giu. A similar

work, entitled: Giu ravai ai buka, was printed at Sydney about 1900.

It contains prayers, the Decalogue, catechism, Psalms i, viii, xxiii,

xxxiv, c, cxxi-cxxxviii; selections from Matthew and John, and hymns,

54 pages.

Griffiths 191:1 (1900)

Mukawa is another language belonging to the British New Guinea group. The name is taken from that of a small village at Cape Vogel, on the south-east coast of British New Guinea, adjacent to the two villages Kapikapi and Menapi. It is spoken by about 1,500 people. Here is stationed, since 1903, the Rev. Samuel Tomlinson. He was ordained deacon 1903, and priest 1904, by the bishop ·of New Guinea. He translated into the Mukawa dialect the Gospel of St. Luke. In 1905 the S.P.C.K. published for him * Ekalesia | ana Pari. | [Portions of the Book of Common Prayer in the Mukawa language.] (2), 181 pages, fcap. 8vo. In the same language the venerable society issued a Psalm and Hymn Book [Giu Pipiya Asi Buka — Salamo ba Tabora]; Preparation for Holy Communion; and a Catechism Book[3].

[3] See, also, The Guardian, May 2, 1913, p. 579, cols. 1, 2.

CHAPTER XLV

THE MELANESIAN MISSION, I

THE Melanesian[1] Mission included

the following island groups, beginning at the extremity furthest from

New Guinea: (1) The Loyalty Islands; (2) New Hebrides; (3) Banks’ Islands;

(4) Torres Islands; (5) North of Fiji, Rotuma; (6) Santa Cruz Islands,

and (7) the Solomon Islands. They are bounded on the east by the Fijis,

and closed in to the westward by Australia and New Guinea. At present

the diocese of Melanesia comprises the northern islands of the New Hebrides,

the Banks’, Torres and

Santa Cruz groups, and the Solomon Islands with Norfolk Island.

The mission was begun by the great Bishop George Augustus Selwyn. Time and again he went from Auckland, New Zealand, to these isles, planting the seeds of Christian love and fellowship. His ultimate aim and that of his successors was the development of a native ministry, guided by the larger experience of white clergy. When the mission college of St. Andrew at Kohimarama, near Auckland, which had been opened in 1860, was broken up the name of the institution, but not the college itself, was transferred to a school on the fertile soil of Mota, Banks Islands, where the Rev. George Sarawia opened a mission in 1869 and a central school for the education of the people of his island. In the early days of the mission this school did excellent work. But, as St. Barnabas College, on Norfolk Island, half-way between Melanesia and New Zealand, became — since 1867 — fully developed, it was so entirely the focus of light that St. Andrew College at Mota waned in importance. The common language, the lingua franca of the mission college, St. Barnabas, however, is Mota. It is akin to the dialects of the northern New Hebrides and to the language of Fiji. It happened that several of the most intelligent of Bishop Patteson’s converts came from this little island, so that it was possible to get translations in that language earlier than in any other. And so it came to be adopted as the training language. It is, of course, a strange tongue to the boys from other islands, but it is a language which expresses the island ideas in a way English would not do. The natives learn it much more quickly than they could English, and their services in the chapel of the college are held in this dialect. Of course all missionaries must learn Mota; but besides that, each more or less devotes himself to the language of the islands with which he has most to do.

Mota[2], called also “Sugarloaf Island,” and at first known as Aumota, is one of the Banks’ Islands[3]. It is the Iona of the Pacific, and was selected in 1860 by Bishop Selwyn — that prince of missionary bishops — as the basis of a mission in that group. The Rev. John Coleridge Patteson remained there for several weeks. The year following Bishop Selwyn resigned the charge of the mission to Mr. Patteson, who was consecrated missionary bishop for Melanesia in Auckland on the festival of St. Matthias, February 24, 1861. Bishop Patteson was one of the rare finds of his predecessor. He was born in London, April 1, 1827, studied at Eton and later at Oxford. In 1855 he went out to New Zealand to assist Bishop Selwyn in his mission work among the South Sea Islanders. Possessing great linguistic talent, the first Melanesian translations were almost wholly his work. He reduced to writing twenty-three of the languages, and compiled and issued elementary grammars of thirteen, and shorter abstracts of eleven others. Most of these, with translations of the New Testament and the Prayer Book, were printed by native pupils of the Melanesian St. Andrew College at Kohimarama, between 1863 and 1868. He was in this work ably assisted by the Rev. Lonsdale Pritt and the Rev. (later Archdeacon) John Palmer, of the Melanesian Mission. His work among the islands was noble and self-denying. He was killed at Nukapu, one of the Reef Islands[4] in Central Melanesia, about thirty miles to the north-east of Santa Cruz, September 20, 1871, by the Melanesians, who mistook his missionary ship for a kidnapper’s craft.

[2] Mota must be distinguished from Motu, one of the languages of British New Guinea, spoken in the Port Moresby district in the coast villages from the mouth of Vanapa River to Round Head. It is, likewise, a Melanesian language. See Codrington, The Melanesian Languages, p. 4. On Motu see the Rev. William George Lawes, Grammar and Vocabularyof the Language spoken by the Motu tribe of New Guinea; Third Edition; 1896; 74 pp.; 8vo. Lawes (1839-1907) was, for many years, a missionary of the London Missionary Society, on Niue and in New Guinea.

[3] The Banks’ Islands, in Southern Melanesia, consist of: (1) Meralava (Star Peak); (2) Gaua (Santa Maria); (3) Mota; (4) Motalava (Saddle Island); (5) Vanua Lava (Great Banks Island) ; (6) Rowa; and (7) Ureparapara (Bligh Island).

[4] The Reef Islands include Materna, Pileni and Nukapu.

Griffiths 113:1 & 113:2

Griffiths 113:3

Bishop Selwyn resigned his see in 1891, and

returned home broken down and lamed for life. He died February 12, 1898;

but to the end of his life he was a missionary at heart. He urged and

encouraged others when they went to take up posts “at the

front.” His successors were Cecil Wilson, 1894-1911, and Cecil

John Wood, 1911.

In 1891 the Melanesian Mission published an edition of portions of the Book of Common Prayer in the Mota language, 208 pages; printed on Norfolk Island. Five years :later an enlarged edition was brought out, including additional Psalms and the liturgical Epistles and Gospels, 352 pages; printed conjointly by the Melanesian Mission Press, Norfolk Island, and Wilsons & Horton, Auckland, N.Z. A supplementary volume, containing various liturgical pieces, was printed on Norfolk Island in 1909, 71 pages.

Griffiths 113:4 (1891)

Griffiths 113:5 (1896)

A catalog of all books published by the Melanesian Mission Press is available online, thanks to Project Canterbury

Griffiths 130:1 (1876, reissued 1888);

Griffiths 94:1 (1882)

Griffiths 94:2 (1905)

[6] See also Codrington, The Melanesian Languages, pp. 408, 409.

Into the Arág language of the Pentecost or Whitsuntide Island a translation of Prayers, Psalms, hymns and Catechism has been printed, made from his native language. Mota, by Thomas Ulgau, assisted by his scholars at Qatvenua, on the north end of the island. The printing was done by the Melanesian Mission Press in 1882[7]. An enlarged edition was published at Auckland, N.Z., in 1904, 143 pages, 8vo. It was prepared by two members of the Melanesian Mission — the Revs. Brittain and Edgell.

Arthur Brittain graduated from St. Augustine’s College in 1878; was ordained deacon in 1881, and priest in 1884. He was missionary in Melanesia from 1881 to 1896. He then left the mission field and went to the United States of America, where he has been rector of several churches. At present he is rector of St. John’s Church, St. Louis, Missouri. — William Henry Edgell graduated from the same college in 1894, was ordained deacon in 1897, and priest 1899. From 1895 until 1905 he laboured as a missionary among the New Hebrides Islands. At present he is missionary priest of the diocese of Auckland.

Griffiths calls this language Raga.

Griffiths 139:1 (1882, untraced)

Griffiths 139:1a (1904)

[7] Ibid., p. 431.

CHAPTER XLVI

THE MELANESIAN MISSION, II

THE Solomon Islands, or archipelago, is a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean, east of New Guinea, about latitude 5°-11°S. The inhabitants are principally Melanesians, and are warlike cannibals. The islands were discovered in 1561 by Alvaro Mendafia de Neyra (1541-96).

“Of the languages spoken in the Solomon Islands

some fall naturally into two groups: those which belong to Ulawa and

the neighbouring part of Malanta, Ugir, San Cristoval and the part

of Guadalcanar adjacent; and those of Florida, the parts of Guadalcanal

opposite, and the nearest extremity of Ysabel. . . . The language of

Duke of York Island, lying far away. carries on the connection of these

languages towards New Guinea, though it does not lie between Ysabel

and that great island”[1].

Griffiths calls this language the Wano or Wango dialect of the San Cristoval language.

[2] Ibid., p. 505.

* E Rine | Inia haatee Rihunai rago | rai Rihunai Mani Dani | ma e Rine inia e ma Sacrament | mana tarainei mai e rine Rihunai rai | Rihunai noai ruma maaea. | London. . . .

64 pages, fcap. 8vo. Title, reverse blank; text, p.

3 foll. Pages 55-64 contain a selection of hymns for congregational purposes.

It is almost safe to assume as translators Archdeacon Richard Blundell

Comins, D.D., and Rev. Robert Paley Wilson, to whom we owe all other translations

of portions of Scripture into Wano. To Dr. Comins is to be assigned

also a small pamphlet in the Fagani dialect of San Cristoval, entitled

Mani Rifunagi. Mission Press, Norfolk Island, 1904. 15 pages. It includes

a few prayers and hymns, and the Decalogue.

Griffiths 186:2 (1904)

[3] Ibid., p. 512. Ulawa is the Ile de contrariété of de Surville (1769).

* Tolaha ni Qaoolana | Mala Ulawa. | Muni Qaoola onioni ani | i Haahulee | na | i Seulehi lou | i nima ni mane. | Portions of the Prayer Book, Ulawa,. Solomon Islands.

214 pages, fcap. 8vo. Title, reverse blank; text, p. 3 foll. This edition includes the liturgical Epistles and many of the Psalms.

The translator, in all probability, was the Rev. Walter George Ivens, missionary priest in charge of S. Mala, with Ulawa, from 1895 to 1909. Since that time he has been organising secretary of’ the Melanesian Mission, and is stationed at present at Kilbinnie, Wellington, N.Z. Ivens graduated from the University of New Zealand, B.A. 1893, and M.A. 1894.

One of the two dialects of Little Mala is

the one spoken at Saa, at the extremity of the island, and with local

variation along the western coast up to Bululaha. It is not very different

from Ulawa, the opinion at Saa being that the Ulawa people have the same

language, but do not speak it right[4]. In 1904 an edition

of portions of the Book of Common Prayer, including most of the Psalms

and other selections from Scripture, was

printed at the Melanesian Mission Press. 168 pages. An enlarged edition,

including the liturgical Epistles, was published in 1907 by the S.P.C.K.,

entitled:

[4] See, further, Codrington, p. 516.

Griffiths 99:2 (1904)

* Tolahai Palona | Mala Saa | Huni Palopalo oni-oni eni | I Hoowa | na | i Seulehi lou | i Nume maai. |

208 pages, fcap. 8vo. Title, reverse blank; text, p. 3 foll. The work of translation was done by Joseph Wate, the earliest convert in Mala. At the age of twelve he was sent, in 1886, to Norfolk Island, there to be educated. He died in 1902; but Walter Ivens continued the work of translation.

The Fiu is spoken on the north-western coast of Mala. Into this dialect

portions of the Prayer Book were translated by the Rev. Arthur Innes

Hopkins, of the Melanesian Mission, and published by the S.P.C.K. in

1909, 112 pages, fcap. 8vo. The title reads:

* Na fata fooala i Fiu | kira fooa dani firi ma ofodani | fainia saulafi i luma aabu. | [Matins, Evensong, Psalms, Collects and Hymns in the Fiu, Mala, dialect, Solomon Islands.]

The hymns (Na nu aabu ki) occupy pp. 89-112.

Hopkins graduated B.A. from St: Catharine College, Cambridge, in 1891.

In 1900 he took up the work of foreign missions, and has been stationed

since then on north-western Mala.

Lau is spoken along the north-eastern coast of Mala, on Suraina, an islet inside the north-eastern reef of Great Mala, and in Romarama and M(w)alede, Port Adam. An edition of portions of the Book of Common Prayer was published in 1903 from the Melanesian Mission Press, 63 pages. The translation was done by Walter Ivens.

Vaturanga is a dialect spoken in the north-western district of Guadalcanar, to the west of Mala. In 1902 portions of the. Book of Common Prayer were published in this dialect by the Melanesian Mission Press, 160 pages, translated by the Rev. Percy Temple Williams, of the Melanesian Mission. The book includes certain Psalms, but omits the liturgical Epistles and Gospels. Williams graduated from Jesus College, Cambridge, B.A., 1890, M.A. 1894. He was missionary in Melanesia from 1895 to 1896 and 1899 to 1902. From 1902 to 1905 he was at Guadalcanar. During the years 1896 to 1898 he was missionary at Bundaberg, Queensland.

Griffiths 189:1

The Florida language is spoken by about 5,000 inhabitants of the island. It is one of those purely local languages, without affiliations to others. This is quite common in Melanesia, where, although the inhabitants with few exceptions belong to the Papuan race, almost as a rule the natives of one island, however small, have a language which the natives of other islands do not understand. Indeed, it has been found — as mentioned above — that on a small island in these groups there have been two or three distinct tongues and tribes of people, who never met without bloodshed.

The language of Florida island has been reduced to writing by the members

of the Melanesian Mission. Roman letters were used for the purpose. The

language is understood by a population of about 20,000 dwelling in neighbouring

islands, as stated above.

Griffiths 39:3; this language is currently known as Nggela or Gela

The translator was actually Alfred Penny (see below).

Na ronoborono | ni kokoeliulivuti. | Kara nia kokoeeliulivuti | tana lei boni tana vale te tabu. | The Book of Common Prayer in the Florida language (Solomon Islands).

(1), 302 pages, fcap. 8vo. The edition omits the introductory matter as well as the Psalter or Psalms of David.

Penny was a member of the Melanesian Mission from 1875 to 1888, stationed on Norfolk Island. He graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge, B.A., 1868, and M.A. 1872 ; was ordained deacon in 1868 and priest in 1869. He returned to England in 1888, and has been for a number of years rector of the Collegiate Church of St. Peter, Wolverhampton, diocese of Lichfield. He is the author of Ten Years in Melanesia, 1887, and of The Head-hunters of Christobal, 1903.

The Santa Cruz is spoken in the Santa Cruz Islands to the north of the New Hebrides. The group has belonged to Great Britain since 1898. The natives are of Papuan stock, with an intermixture of other blood. In 1894 the Melanesian Mission Press issued an edition of portions of the Book of Common Prayer, containing also a number of Psalms. 126 pages. The translation was made by the. Rev. A. E. C Forrest and other members of the Melanesian Mission.

Torres is the language of the Torres group, to the north of the New Hebrides, consisting of four inhabited islands with a. population of about 1,500. The translations of Scriptures. or Liturgy are all in the dialect of Lo. About the year 1897 the Rev. Leonard Philip Robin, of the Melanesian Mission, translated the liturgical Epistles and Gospels, 133 pages, with an appended table. Text printed in paragraphs. The book was printed by the Melanesian Mission Press .. Ten years later, in 1907, the same press issued an edition of portions of the Book of Common Prayer, 45 pages. Robin is a graduate of Hertford College, Oxford, 1881. He was. missionary in Melanesia, 1888-90; at Torres Islands, 1890-99, and organising secretary for the Melanesian Mission,. 1899-1905.

Griffiths 179:2 (1894) and 179:3 (1897)

Griffiths 179:4 (1907)

CHAPTER XLVII

THE MAORI OF NEW ZEALAND

NEW ZEALAND,

a British Colonial Dominion since 1907, has a coloured population of

53,000, including 2,300 Chinese. and 6,500 Maori half-castes. The islands

(North and South Island) were called New Zealand by Abel Jansen Tasman,

who, in 1642, reached its shores in the Heemskirk, but did. not land.

The real explorer of the group was Captain James Cook. Maori, the language

of the aborigines of New Zealand, has an alphabet consisting of only

14 letters. It is written with roman characters. The Maoris are the purest

branch of the Polynesian race. They proved from the very beginning especially

accessible to Christian influence. Samuel Marsden (1764-1838) was a government

chaplain at Port Jackson. While in Botany Bay he fell in with some Maoris

and became inspired with the idea of bringing Christianity to their islands.

After several vain appeals, the C.M.S. sent in 1814 a party, of which

the Rev. Thomas Kendall was. one of the chief men. This party was led

by Marsden and worked under the protection of Duaterra[1],

a native chief. Marsden, “the Apostle

of New Zealand,” made seven missionary visits to these islands

extending over twenty-three years. For many years the mission

made but slow progress, chiefly due to the murderous tribal wars. Still,

cruel experience and the persevering preaching of the missionaries gradually

checked the fighting, and by the year 1839 it could be claimed that peace

and Christianity were in the ascendant.

[1] Wynne calls him Ruaterra.

Kendall returned to England in 1820 accompanied by two native chiefs, and with the help of Professor Samuel Lee, of Cambridge, the Maori language was reduced too writing and a grammar was published. Two years later the first resident clergyman, the Rev. Henry Williams. (1792-1867), formerly a naval lieutenant, was ordained and appointed to New Zealand by the CM.S. It was through his influence and that of his younger brother, William Leonard Williams (1800-79), a surgeon, that the Maoris in 1840 submitted to the sovereignty of Queen Victoria and that a native war was avoided. The translation of the liturgy into the Maori language was above all the work of the younger Williams, who in later years (1859-79) became the first bishop of Waiapu.

In Christianity Among the New Zealanders, the author, Bishop Williams, states on p. 117 :

“The work of translation was proceeding gradually, and the increasing wants of the natives were now in some small measure supplied by a second little volume which was printed in New South Wales during the time of the commotions which were going on in the Bay of Islands in the early part of the year 1830. It contained the first three chapters of Genesis, portions of the Gospels of St. Matthew and St. John, a part of the first Epistle to the Corinthians, .and parts of the Liturgy and Catechism.”

And on p. 164 :

“The work of translation had been steadily advancing,

and in the early part of the year 1833 an edition of 1,800 copies of

another work was printed in New South Wales, containing a large portion

,of the services of the Prayer Book, and about half of the New Testament.”

Griffiths 106:1 (1830); 106:2 (1833)

[2] Particulars about the editions of 1830 and 1833

are given in Darlow and Moule, Vol. II, p. 1071, No. 6644.

In 1836 Mr. Williams had ready for publication a complete translation of the New Testament and of the Book of Common Prayer. The translator was fortunately able to superintend the printing at Paihia, the C.M.S. having sent out in 1834 a printing press in charge of Mr. William Colenso. The printing of an edition of 3,000 copies of the liturgy was ’begun, but no sooner was the Order for Morning and Evening Prayer completed, than it was found necessary to bring that portion into use at once, and no less than 33,000 copies of this were struck off before the complete work could be brought out in 1838. In all of this translational work Williams was ably assisted by the Rev. (later Archdeacon) Robert Maunsell who had joined the Mission twelve years .later than Henry Williams.

The period of organisation of the Church in New Zealand began with the

appointment of George

Augustus Selwyn (1809-78) as primate of New Zealand

(1841-69). He was one of the most remarkable men among the English clergy

of the last century; a man of affairs, endowed with physical energy

and mental vigour, and a most admirable talent for organisation.

Griffiths 106:3 (1839)

In 1840 there was published by the C.M.S. press at Paihia: Ko te Pukapuka | o nga Inoinga, | me te | minitatanga | o nga Hakarameta, | ko | era tikanga hoki o te hahi, | ki te ritenga | o te hahi o Ingarani. 218 pages, 2 columns to the page, 8vo. Follows Part II: Ko | nga Waiata | a Rawiri. | Katahi ka taia ki te reo Maori. | . . . 141, (1) pages; i.e., a version of the Psalter, first printed in 1837, the work of :Maunsell, who in later years became the chief translator of the Old Testament into Maori. He had joined the :Mission in 1834 and died at Auckland, April 19, 1894, in his eighty-fourth year.

The Psalter in this 1840 edition is followed by twelve unnumbered pages

containing forty-two hymns, with the general heading: Ko nga himene.

Griffiths 106:4; also Griffiths 106:5-7 (all 1841)

In 1843 Bishop Selwyn appointed a translation

syndicate, Williams, Maunsell, Richard Taylor and others, which met at

Waimato in May, 1844, to revise the translation previously made by W.

L. Williams. The committee continued in session there, the bishop presiding,

until October of the same year, the Rev. Henry Williams in the meanwhile

taking his brother’s place at Turanga. The book was printed at Ranana

and published in 1848 by the S.P.C.K., entitled: Ko te pukapuka o nga

inoinga, me era atu tikanga, | whakakaritea e te hahi o ingarani, mo te

minitatanga o nga hakarameta, o era atu ritenga hoki a te hahi: me nga

waiata ano hoki a rawiri, me te tikanga mo te whiriwhiringa, mo te whakaturanga,

me te whakatapunga o nga Pihopa, o nga Piriti, me nga Rikona. xxii, 321

pages, 12mo. A second edition, revised and corrected by Mr. Williams,

appeared in 1852. ii, 432 pages, 12mo. This is the first complete Maori

Prayer Book, including the Psalter, etc. Later editions were put out in

1859; ii, 432 pages, 24mo; and a revision of this in 1878. Another

new edition appeared in 1883; xxiii, 459 pages, 8vo. An edition in

16mo was put out in 1901 and another, in 24mo, 1902.

Griffiths 106:8 (1848)

Griffiths 106:9 (1852, reset 1859 & 1876)

Griffiths

106:10 (1877, ordinal added 1890)

Griffiths 106:11 (1883, reissued 1887,

1901)

The latest edition, printed in 1909 reads:

* Te Pukapuka | o nga Inoi | me era atu Tikanga | a te Hahi o Ingarani | mo te minitatanga | o nga Hakarameta, | o era atu ritenga Hoki a te Hahi; | me nga Waiata ano hoki a rawiri; | me te Tikanga | mo te Momotu | I te Pihopa, | te Piriti, | te Rikona. Ranana: . . . 1909.

xxviii, 491, (1) pages, 24mo.

Griffiths 106:12 (1890, many reissues through 1956)

CHAPTER XLVIII

THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

THE Hawaiian Islands are the extreme north-western group of Polynesia.

They were discovered by Captain James Cook in 1778. Some thirty years

later, in 1821, the first English missionaries, Revs. George Bennett

and Daniel Tyerman (died 1828), of the London Missionary Society, .and

the Rev. William Ellis, of the same society (1794-1872), then a missionary

at Tahiti, came to the islands, and through their efforts and those of

early American missionaries the language was put into a written shape,

a task of no little difficulty.

In 1870 Bishop Staley retired, and two years later, on February 2, 1872, the Rev. Alfred Willis was consecrated second bishop of Honolulu. In the face of financial and other difficulties, the new lord bishop of Honolulu remained at his post until the year 1902, when upon the annexation of Hawaii as a territory to the United States of America, the work of the S.P.G. and the Church of England was transferred to the American sister, the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States. Since 1902 Willis has been missionary bishop in Tonga, diocese of Polynesia, and is living at Nukualofa, Friendly Islands.

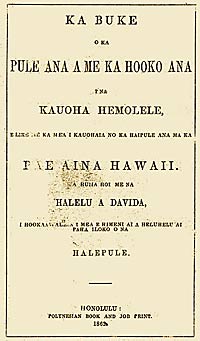

In 1883 the S.P.C.K. published for Bishop Willis a revised and enlarged edition of the Liturgy, being the entire Book of Common Prayer, excepting the Articles, entitled:

* Ka Buke | o ka | Pule ana a me ka hooko ana | i ka | Lawelawe ana | na Sakarema a me | na oihana e ae o ka Ekalesia | e like me ka mea i Kauohaia e ka Ekalesia | Enelani. | A me | ke ana a me ka oihana o ka hoolilo ana, ka poni | ana, a me ka hoolaa ana | na Bihopa, na | Kahuna, a me na Diakona, | i unuhiia iloko o ka olelo Hawaii no ka Ekalesia | ma ka | pae aina Hawaii. | Na | Halelu a Davida, | i kikoia i mea e himeni ai a heluhelu ai paha | iloko o na halepule. | (Prayer Book in the Hawaiian language for use in the Sandwich Islands.) | Ladana: Hoolaha ana | ka Naauao Kristiano. 1883.

xlii, (1), 468 pages, 24mo.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND AUTHORITIES CONSULTED

ALEXANDER, W. D. Review of a Pastoral Address by T. N. Staley, containing a reply to some of his charges against the American Protestant Mission to the Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu, ’64. 8vo.

ANDERSON, R. The Hawaiian Islands: Their Progress and Condition under Missionary Labours. 3rd edition. Boston, ’65. Illus. Portraits. Plates. Maps. 12mo.

ARMSTRONG, E. S. History of the Melanesian Mission. Lo. ’00. 8vo.

AWDRY, F. E. In the Isles of the Sea: the story of fifty years in Melanesia. Lo. ’02. Illus. Portraits. Plates. 8vo.

—— The Story of a Fellow-Soldier [Bishop J. C. Patteson]. La. ’75. 8vo.

BALLOU, H. M., and G. R. CARTER. The History of the Hawaiian Mission Press, with a Bibliography of the Earlier Publications. Facsimiles. In Gilman, G. D., Journal of a canoe voyage along the Kanai Palis. Honolulu, ’08.

BANKS, M. B. Heroes of the South Seas. N.Y. [’96]. Plates. 12mo.

BELCHER, D. The Mutineers of the Bounty and their Descendants in Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands. N.Y. ’71. Portraits. Plates. Map. 12mo.

BIRT, H. N. Benedictine Pioneers in Australia. St. Louis, ’11. 2 vols. Portraits. 8vo.

BRENT, C. H. With God in the Philippine Islands. Concerning the Christian peace. A pastoral letter. ’02. 12mo.

BRIGHAM, W. T. A Catalogue of Works published at, or relating to, the Hawaiian Islands. In Hawaiian Club Papers, pp.63-115. Boston, ’68.

BROWN, G. Melanesians and Polynesians: Their Life-Histories Described and Compared. Lo. ’10. Plates. 8vo.

CARLETON, H. The Life of Henry Williams, Archdeacon of Waimate. Auckland, New Zealand, ’74. 2 vols. 8vo.

CHALMERS, JAMES, of New Guinea. His Autobiography and Letters. [Edited] by R. LOVETT. N.Y. (’02 ?]. Portraits. Plates. Maps. 8vo.

—— Pioneering in New Guinea. Lo. ’87. Illus. Map. 8vo. New edition. ’95.

CHARLES, ELIZABETH. Three Martyrs of the Nineteenth Century. Studies from the lives of Livingstone, Gordon and Patteson. Lo. S.P.C.K. ’85. Sm. 8vo. New edition. ’13.

CHIGNELL, A. K. An Outpost in Papua. . . . Lo. ’11. Portraits. Plates. 8vo.

—— Twenty-one Years in Papua. A history of the English Church mission in New Guinea [’91-’12]. Lo. ’13. Illus. Plates. Map. 8vo.

CHURCHILL, W. The Fale’ula Library: a Polynesian Bibliography. In Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, Vol. XLI [’09]. N.Y. ’09· Pp. 305-343.

—— The Polynesian Wanderings: Tracks of the Migration deduced from an Examination of the Proto-Samoan content of Efaté and other languages of Melanesia. Washington, ’11. Maps. [Carnegie Institution of Washington. Publication. No. 134.} 8vo.

COAN, TITUS. Life in Hawaii: an Autobiographic Sketch of Mission Life and Labours [’35-’81]. N.Y. [’82]. Portrait. 12mo.

CODRINGTON, R. H. The Melanesian Languages. Oxford, ’85. Maps. 8vo.

—— The Melanesians: Studies in their Anthropology and Folklore. Oxford, ’91. Illus. Folded map. 8vo.

—— and J. PALMER. A Dictionary of the Language of Mota, Sugarloaf Island, Banks Islands. Lo. ’96. Sm. 8vo.

COLLIER, J. Sir George Grey, Governor, High Commissioner and Premier. An historical biography. Christchurch, N.Z., ’09. Portraits. [The makers of Australia.] 8vo. — Relates to South Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

COUSINS, G. The Story of the South Seas. Lo. ’94. Illus. Portraits. Plates. Sm. 4to.

COWAN, J. The Maoris of New Zealand. Christchurch, New Zealand, ’10. Illus. Portraits. Plates. Map. [The Makers of Australia.] 8vo.

CURTEIS, G. H. Bishop Selwyn of New Zealand, and of Lichfield. A sketch of his life and work, with gleanings from his letters, sermons and speeches. Lo. ’89. Portrait. 8vo.

DAVIDSON, R. T., Archbishop of Canterbury. Captains and Comrades in the Faith. . . . Lo. ’11. 8vo. And here, Chapter 3 (pp. 27-37): George Augustus Selwyn.

DOUGLAS, SIR ARTHUR P. The Dominion of New Zealand. Boston, ’09· Plates. Maps. [The All-Red series.] 8vo.

DOUGLAS, SIR ROBERT K. Europe and the Far East. Cambridge, ’04. Sm. 8vo.

EDEN, C. H. Australia’s Heroes: being a slight sketch of the most prominent . . . men who devoted their lives . . . to the development of the Fifth Continent. 3rd edition. Lo. [1883]. Map. Sm. 8vo.

ELKINGTON, E. WAY. The Savage South Seas. . . . Lo. Black, ’07. Plates. Map. 8vo.

ELLIS, WM. The American Mission in the Sandwich Islands: a vindication and an appeal in relation to the reformed Catholic Mission at Honolulu. Lo. ’66. 8vo.

FREER, W. B. The Philippine Experiences of an American Teacher; a narrative of work and travel in the Philippine Islands. N.Y. ’06. Plates. Map. 12mo.

GAGGIN, J. Among the Man-Eaters. Lo. ’00. [The. Over-Seas Library, 8.] Sm. 8vo. — Sketches in the Fiji and Solomon Islands.

GRIBBLE, J. B. “Black, but Comely"; or, Glimpses of Aboriginal Life in Australia. Lo. [’74]. 8vo.

GRIMSHAW, B. E. Fiji and its Possibilities. N.Y. ’07. Portraits. Plates. Facsimile. [The Geographical Library.] 8vo. — English title: From Fiji to the Cannibal Islands.

GUPPY, H. B. The Solomon Islands and their Natives. Lo. ’87. Plates. Map. L. 8vo.

HALE, M. B. The Aborigines of Australia: being an account of the institution for their education at Poonindie, in South Australia. Lo. ’89. 8vo.

HENDERSON, G. C. Sir George Grey, Pioneer of Empire in Southern Lands. Lo. ’07. Portraits. Plates. Maps. Facsimile. 8vo.

HOW, F. D. John Selwyn, Bishop of New Zealand and Melanesia. Lo. ’99.

HOWITT, A. W. The Native Tribes of South-East Australia. Lo. ’04. Illus. Plates. Maps. Table. 8vo.

HUNNEWELL, J. F. Bibliography of the Hawaiian Islands. Boston, ’69. Illus. 4to.

INGLIS, J. In the New Hebrides: Reminiscences of Missionary Life and Work, especially on the Island of Aneityum, from 1850 till 1877. Lo. ’87. Map. Portrait. 8vo.

Isles that Wait, The, by a lady member of the Melanesian Mission. Lo. ’12. 12mo.

JACOBS, H. New Zealand. Containing the dioceses of Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin, Nelson, Waiapu, Wellington and Melanesia. Lo. [’87]. Portrait. Map. [Colonial Church Histories.] Sm. 8vo.

JENKS, A. E. The Bontoc Igorot. Manila, ’05· Plates Map. [Philippine Islands. Ethnological survey. Publications. Vol. 1.] 8vo.

JENKS, E. History of the Australasian Colonies. Cambridge. ’95· Map. [Cambridge Historical Series.] Sm. 8vo.

LAMBERT, J. C. Missionary Heroes in Oceania. True stories of the intrepid bravery and stirring adventures of missionaries. . . . Philadelphia, ’10. 8vo.

LAWES, W. G. Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language spoken by the Motu Tribe of New Guinea. 3rd edition. Sydney, ’96. 8vo ..

MACDONALD, D. Oceania: Linguistic and Anthropological. Melbourne, ’89. Plates. 8vo.

—— South Sea Languages. 3 vols. Melbourne. 8vo. — (1) New Hebrides linguistics; (2) Studies on the languages of the New Hebrides and other South Sea islands; (3) The Oceanic languages.

MCFARLANE, S. The Story of the Lifu Mission. Lo. ’73. Plates. Map. 4to.

MACGREGOR, SIR WILLIAM. British New Guinea: Country and People. Lo. ’97. Illus. Map. [Royal Geographical Society.] 8vo.

MACKAY, J. A. K. Across Papua .... N.Y. ’09. Portraits. Plates. Map. 8vo.

MACKELLAR, C. D. Scented Isles and Coral Gardens. N.Y. ’12. Plates. 8vo.

MACKINLAY, W. E. W. A Handbook and Grammar of the Tagalog Language. Washington, ’05. Facsimile. Tables. 8vo.

MARAU, C. Story of a Melanesian Deacon: Clement Marau. Written by himself. Translated by the Rev. R. H. Codrington. Lo. ’94. Illus. Portrait. 8vo.

MARSDEN, J. B. Samuel Marsden. Lo. ’58.

MATTHEWS, C. H. S. A Parson in the Australian Bush. Lo. ’08. Plates. Map. Sm. 8vo.

MONTGOMERY, H. B. Christus Redemptor: an outline study of the island world of the Pacific. N.Y. ’06. Map. [United Study of Missions.] 12mo.

MONTGOMERY, H. H. The Light of Melanesia. A record of thirty-five years’ Mission Work in the South Seas, etc. Lo. ’96. 8vo.

MURRAY, A. W. Forty Years’ Mission Work in Polynesia and New Guinea, 1835 to 1875. Lo. ’76. Illus. Maps. Language sheet. Sm. 8vo.

MURRAY, A. W. The Martyrs of Polynesia. Memorials of Missionaries. Lo. ’85. Map. 8vo.

MURRAY, J. H. P. Papua, or British New Guinea. N.Y. ’12. Plates. Map. Bvo.

MURRAY, T. B. Pitcairn: the Island, the People, and the Pastor; with a short account of the mutiny of the Bounty. 2nd edition. Lo. ’53. Illus. Portraits. Plates. Map. Sm. 8vo. Same. 12th edition. To which is added a Short Notice . . . of Norfolk Island. Facsimile. [’85.]

PAGE, J. Bishop Patteson, the Martyr of Melanesia. N.Y. ’88. Illus. Map. 16mo.

—— Among the Maoris. Lo. ’94. 8vo.

PATTESON, JOHN COLERIDGE. Life of Bishop Patteson. Lo. ’72. Illus. Portrait. 16mo.

PENNY, A. Ten Years in Melanesia. Lo. ’88. Illus. 12mo.

PIERCE, C. C. The Races of the Philippines-The Tagals. Philadelphia, ’01. [American Academy of Political and Social Science Publications, 306.] 8vo.

RAY, SIDNEY H. A Comparative Vocabulary of the Dialects of British New Guinea. Lo. ’89. 8vo.

—— Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits. Vol. III. Linguistics. Cambridge, ’07. Map. 4to.

RAY, SIDNEY H., and A. C. HADDON. A Study of the Languages of Torres Straits, with Vocabularies and Grammatical Notes. In Royal Irish Academy Proceedings, 3rd series. Vol. II, pp. 463-616; IV, pp. 119-373. Dublin, ’9l, ’98.

RIBBE, C. Zwei Jahre unter den Kannibalen der Solomo-Inseln, Dresden, ’03. Illus. Plates. Maps. 4to.

RUSDEN, G. W. History of New Zealand. Lo. ’83. 3 vols. Map. Plan. 8vo.

SCHMIDT, W. Die Sprachlichen Verhaltnisse Oceaniens (Melanesiens Polynesiens, Mikronesiens und Indonesiens) in ihrer Bedeutung für die Ethnologie. In Mittheilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien. Band 29, pp. 245-258. Wien, ’99.

—— Ueber das Verhältniss der Melanesischen Sprachen zu den polynesischen und untereinander. In Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna. Philosophisch-historische Classe. Sitzungsberichte. Band 141, Abhandlung 6. Wien, ’99.

—— Die Jabim-Sprache (Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) und ihre Stellung innerhalb der Melanesischen Sprachen. Ibid. Band 143, Abhandlung 9. Wien, ’01.

SEIDENADEL, C. W. The First Grammar of the Language spoken by the Bontoc Igórot, with a Vocabulary and Texts, Anthology, . Folk-lore, Historical Episodes, Songs. Chicago, ’09. Portraits. Plates. L. 8vo.

SELIGMANN, C. G. The Melanesians of British New Guinea . . . Cambridge, ’10. Illus. Plates. Maps. Table. 8vo. — An ethnological study.

SHORTLAND, E. Maori Religion and Mythology. Illustrated by translations of traditions, Karakia, etc. Added, Notes on Maori tenure of Land. Lo. ’82. Sm. 8vo.

SMITH, S. P. The Peopling of the North: Notes on the ancient Maori history of the northern peninsula, and sketches of the history of the Ngati-Whatua tribe of Kaipara, New Zealand: “Heru-Hapainga.” Wellington, ’96, ’97. 8vo.

SMITH, WILLIAM. Journal of a Voyage in the Missionary Ship Duff to the Pacific Ocean in the years 1796, 7, 8, 9, 1800, 1, 2, &c. : comprehending authentic and circumstantial narratives of the disasters which attend the first effort of the “London missionary society.” . . . With an appendix, containing interesting circumstances in the life of Captain James Wilson, the commander of the Duff. . . . N.Y. 1813. 16mo.

STALEY, T. N. Bishop of Honolulu. A few questions with respect to the Episcopal Mission to the Kingdom of Hawaii briefly answered. Cambridge, Mass., ’66. 8vo.

—— Five Years’ Church Work in the Kingdom of Hawaii. Lo. ’68. Portraits. Plates. Map. Sm. 8vo.

—— A Pastoral Letter ... with Notes and a Review of the Recent Work of the Rev. R. Anderson, D.D., entitled: “The Hawaiian Islands.” Honolulu, ’65. 8vo.

STUNTZ, H. C. The Philippines and the Far East. Cincinnati, ’04. Illus. Portraits. Plates. Maps. 12mo.

SYMONDS, E. The Story of the Australian Church. Lo. ’98. Map. [Colonial Church Histories.] Sm. 8vo.

SYNGE, S. Albert Maclaren. Lo. S.P.G. ’08.

THOMAS, N. W. Natives of Australia. Lo. ’06. Plates. Map, (The Native Races of the British Empire.] 8vo.

TUCKER, H. W. Memoir of the Life and Episcopate of George Augustus Selwyn, Bishop of New Zealand, 1841-67; Bishop of Lichfield, 1867-78. Lo. ’79. 2 vols. Portraits. Plates. Maps. 8vo.

TURNER. GEORGE. Samoa a Hundred Years Ago, and Long Before. Together with notes on the cults and customs of twenty other islands in the Pacific. Lo. ’84. Plates. Maps. Sm. 8vo.

TYERMAN, D., and G. BENNETT. See above, Bibliography to Part IV. WALKER, H. W. Wanderings among South Sea Savages and in Borneo and the Philippines. Lo. ’09. Portraits. ,Plates. 8vo.

WILLIAMS, W., Bishop of Waiapu. Christianity among the New Zealanders. Lo. ’67. Illus. Sm. 8vo.

WILLIAMSON, R. W. The Mafulu Mountain People of British New Guinea. Lo. ’12. 8vo.

WILSON, WM., First Mate of the Ship Duff. A Missionary Voyage to the Southern Pacific Ocean, in the Years 1796, 1797, 1798, in the Ship Duff, commanded by Captain James Wilson. . . . Lo. 1799. Plates. Map. L. 8vo.

WISE, B. R. The Commonwealth of Australia. Boston, ’09. Plates. Map. [The All-Red series.] 8vo.

WOLLASTON, A. F. R. Pygmies and Papuans. Lo. ’12. 8vo.

WOOLLCOMBE, H. S. Beneath the Southern Cross: being impressions gained on a tour through Australasia and South Africa on behalf of the Church of England Men’s Society. Lo. ’13. Plates. 8vo.

WORCESTER, D. C. The Philippine Islands and their People. N.Y. ’99. Illus. Plates. Maps. 8vo.

WRIGHT, H. M. A Handbook of the Philippines. Chicago, ’07. Portraits. Plates. Maps. 12mo.

YONGE, C. M. Life of John Coleridge Patteson, Missionary Bishop of the Melanesian Islands. 5th edition. Lo. ’75. 2 vols. 8vo.